Tattoos as Body Reclamation

My parents were strict compared to those of my peers. I’m the oldest of five kids, so as is often the case, they upheld the most stringent rules with me while they figured out how to parent. When I was young, this played out as not being allowed to watch TV, not being permitted to have sleepovers, and not being allowed to spend time unsupervised in public places with friends. As I got older, the restrictions grew to include limitations on how I could physically express myself. I wasn’t allowed to get any piercings outside of one hole in each ear, my bra straps had to be hidden, and tattoos were completely off the table. When I inevitably broke smaller rules like spending time with friends at a public park at night, my parents grounded me. But the punishment for permanent body modifications was more severe: my parents told me they’d withdraw all financial support, including their contribution towards my college tuition later on. I had no desire for tattoos, but I did desperately want to pierce my left nostril. They wouldn’t budge, so I got my belly button pierced just after turning 18 because it would be possible to hide. (I successfully hid it until I was 21.)

At some point during my adolescence, my parents also began to teach me that my body was inherently sexual, regardless of whether or not I was actually acting sexual, a common experience of young girls. I remember my dad telling me “the boys will be chasing after you some day,” and my mom telling me “all guys want is sex, and they’ll say and do anything to get it.” I know that both of them were coming from a place of care and protection for me, but it changed how I began to view both my body and the boys and men in my life. I simultaneously grew to crave physical validation from my peers, as well as hate and fear it. I developed an inherent distrust in all boys/men that I’m still working to unlearn today.

My family household had healthism undertones but thankfully wasn’t outwardly seeped in body-size-focused diet culture. But that harm was still done outside of the house. By seventh grade, I’d developed anti-fat bias, and by 10th grade, I’d begun trying to control my body through food restriction and exercise. I wanted to take away my curves so that I’d be less “hot” and therefore, any attention I received from guys would be genuine interest for me as a person instead of just my body (like my parents taught me).

In freshman year of college, I went on to develop a full-blown eating disorder, most closely resembling orthorexia. After two years of pseudo-recovery in treatment forced by my parents (again, they threatened to withdraw all financial support if I did not comply), I decided that I was ready to actually try to recover for myself. So, I entered residential treatment.

There I began unpacking everything I’d internalized that landed me 3,000 miles away in a facility where I wasn’t allowed to eat, move, or go to the bathroom without supervision.

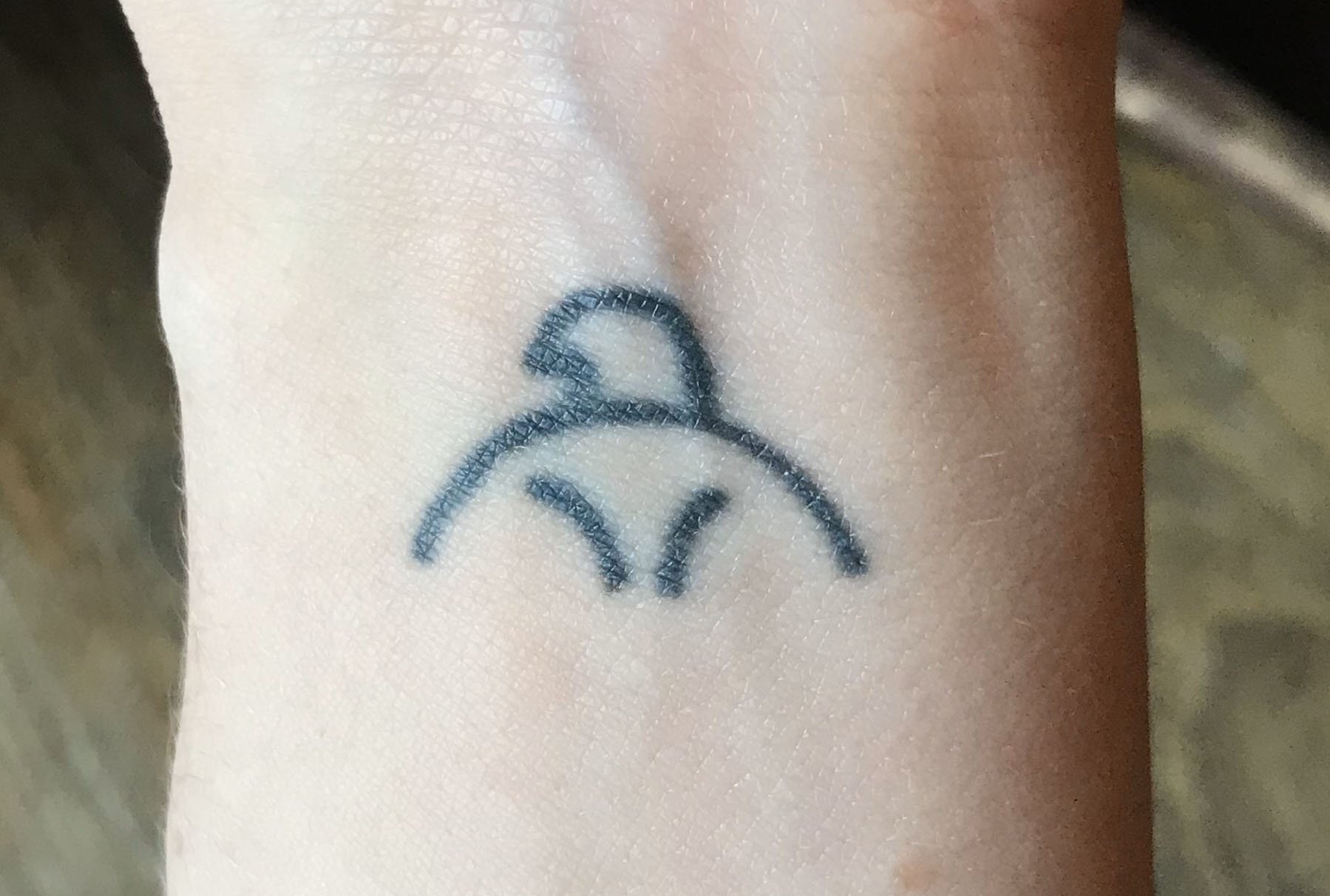

I graduated from residential treatment in June of 2013, and then from college a year later. In November of 2014, I got my first tattoo: an eagle on my left wrist. To me it’s a reminder to own my inner power – to not give it away to other people or let them take it from me. This means that I’ll know I’m smart because I think I am, not because someone else tells me I am. I’ll know I’m kind because I think I am, not because someone else tells me I am. I’ll know I’m pretty because I think I am, not because the beauty industry does or doesn’t tell me I am. I’ll know my body is good, because I think it is, not because diet culture tells me it is or isn’t. Etc. (I don’t remember where I found this symbolic meaning, and truthfully, I’m a bit nervous to dig back into my original Facebook post in case the source is insensitive to Native American culture and tradition.) My younger sister went with me to get the tattoo, and when we got home and sat down for family dinner, my dad asked us what we’d been up to. I tried to get around answering honestly because I was anticipating it going poorly, but when he persisted, I told him. He walked out of the room in silence and didn’t make eye contact with me for several days, eventually directly voicing his disapproval.

Almost 9 years later, I’m covered in tattoos. Truthfully, I’ve lost count. Maybe I have around 50? I have the Alice in Wonderland quote “we’re all mad here” that reminds me that everyone has mental health – some people are just more open about it than others. I have a semicolon in memory of my former college tennis teammate who died by suicide. I have a skull wearing the flower crown my therapist gave me at my residential treatment graduation ceremony because residential truly saved my life. I have the moon phases as a reminder to think of my period as my “moon time” instead of a dreaded time of the month and a reminder of my “failure” to keep my sick eating disorder body. (Did you know that our periods are connected the moon cycle? Because I did not before treatment!) I have an eye that prompts me to be “awake” to the greater picture and not get caught up in the superficial and hustle of our modern society. I have a monkey to remind me of the shamanic meditation journey I did in treatment to meet my power animal (a monkey). I have an hourglass to emphasize that time is fleeting, and I don’t want to waste any of my limited time or energy on self-judgment, whether it be my body, career progress, relationship status, etc. Many of my tattoos, like the ones mentioned above, have individual meaning. But many also do not – they are beautiful additions to my ever growing art collection.

Once I got a (metaphorical) taste of body autonomy after years of body restriction, I wanted more. Getting tattoos felt – and still feels – like I was reclaiming my body from my parents and society at large (diet culture, the beauty industry, the patriarchy, capitalism, etc.).

Now, I get to control how I express myself and some of how the world sees me, in a way that doesn’t cause myself harm like the eating disorder did. I get to adorn my body with permanent art that serves as a reminder to be my authentic self, regardless of what others around me think.

From the very beginning, my parents’ intentions were good – they wanted to help me developmentally grow through reading instead of watching TV that is so often grounded in harmful stereotypes, protect me from potentially unsafe social situations where there would be no parental supervision, and prevent me from making any permanent alterations to my body while I was young and my mind, views and values were still developing. But the unintended impact was that I didn’t feel like I had full bodily autonomy until I was 22 years old. I understand why they set the rules they did, and I don’t know exactly how I would’ve liked them to parent instead. I’m grateful that I have no desire to have children, because parenting seems really really hard.

Today my mom is much more supportive of my tattoos because she recognizes them as a healing-based interest of mine. She has no interest in getting any herself, but her body modification worldview has evolved as my sister and I have both explored self-expression with piercings and tattoos. My dad and I don’t directly talk about them, but he no longer has such a strong reaction when he sees them. I’ve also been able to show him that my tattoos have not hindered my professional growth – one of the primary reasons behind his aversion to tattoos. Besides, all that truly matters is that I like my tattoos. And, let me tell you, I really really do.