Orthorexia & Chinese American Identity: How White Supremacy & Colonialism Warped by Constructs of Health

Written by Alexandra Xu

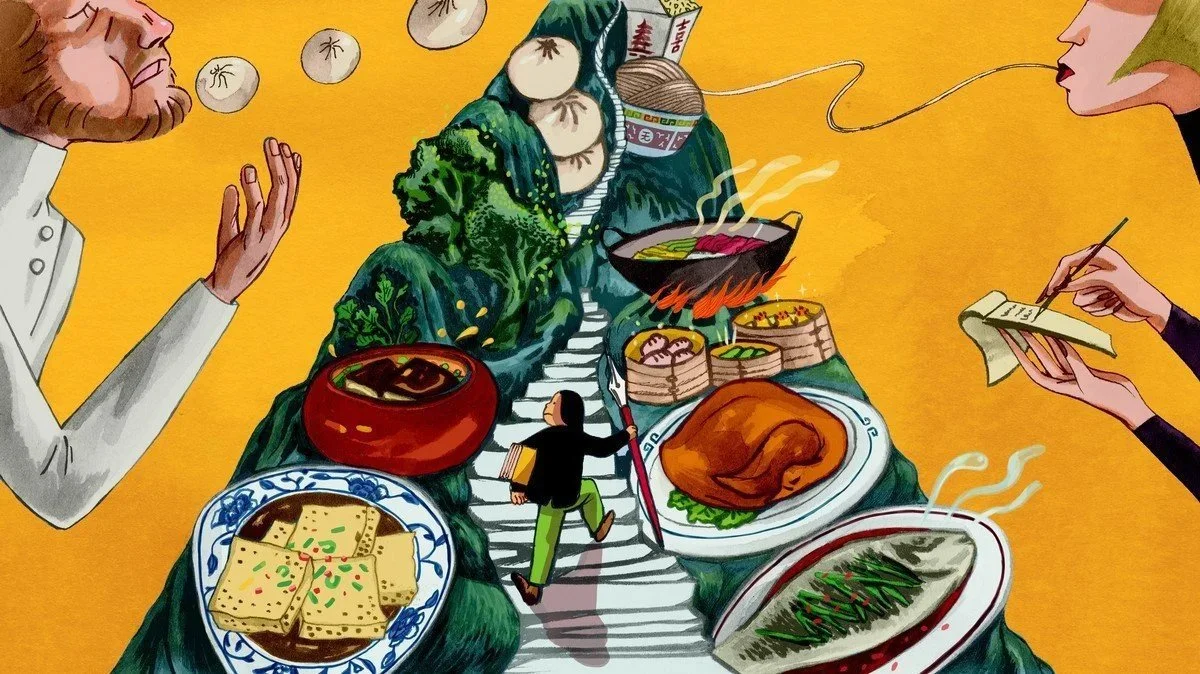

Under the backdrop of a murky sky, I surged through the streets of New York City, feet thumping against the fissured sidewalk. Whenever I reached a red light, a ponderous dread swelled through my chest; I instinctively checked my iPhone’s Health app, surveilling my step count. Following this overwrought commute, I at last beheld my destination: Lucky Lee’s, a self-professed “clean” Chinese restaurant.

Accompanied by my mother, I entered the brightly lit establishment, taking in the baby blue walls and elegant bamboo lights. Emblazoned on lofty TV screens was the menu, touting everything from grass-fed beef and broccoli to grain-free dumplings. I experienced a rush of intense pleasure—a solacing sense of entering a haven for the fervently health-conscious. Surely these people, if no one else, would grasp my dietary habits.

We first sampled the cauliflower “fried rice”—incredibly underwhelming, but I feigned enjoyment. Chewing gingerly, I glanced around; with the palpable exception of my immigrant Chinese mother and I, every single person in this place was white.

Of course, I was aware of the impassioned retaliation that Lucky Lee’s had kindled.

I understood deep down that this was textbook cultural appropriation, rooted in the vilification of Chinese cuisine (or a monolithic, reductionist conception of Chinese cuisine)—indeed, Chinese people—as “dirty.”

At one point, the restaurant’s owner, a white woman, even darted over to engage us in zealous dialogue, and I discerned with unease that we were the token exemplars of “diversity.” In her eyes, our very presence likely affirmed that she wasn’t causing harm; she psychologically transformed us into emblems of favorable Chinese sentiment, attenuating her own sense of culpability.

Growing up in a predominantly white school district, I scarcely contemplated my Asianness beyond the occasional quip about being “the Asian friend.” I could understand Mandarin to a certain extent but was virtually incapable of speaking, writing, or reading the language. Dining at Lucky Lee’s, encircled by white folks with no cognizance of my culture (indeed, a culture I feared I did not fully grasp), seemed to corroborate that I was a fraud.

Far worse was the rapturous satisfaction I derived from believing that I was eating “clean.” The knowledge that I was avoiding ingredients that would avowedly corrupt my body, my fundamental constitution, supported the identity I’d fabricated as “the health nut” and conferred me incredible comfort.

My fixation with “wellness” dated back to several years prior. At the time, I was in fourth grade and thus wholly engulfed in the Rainbow Loom craze of the early 2010s. Day in and day out, I wove intricate bracelets while partaking in rigorous classical piano training. These pursuits led me to develop forearm tendonitis. When physical therapy proved relatively futile, my family turned to “clean eating” to alleviate my forearm inflammation; proponents of holistic wellness have long professed that “food is medicine,” so we figured that adopting particular patterns of eating could address the root cause of my injuries.

At first, I hardly took this new dietary regime seriously, jokingly airing grievances about my parents’ green smoothies and draconian restrictions on “junk food.” Upon entering middle school, however, I developed a newfound consciousness of bodies in general. Hushed conversations following mandatory weigh-ins during gym class; frenzied efforts to edit images before posting them on Instagram—thus began my efforts to surveil and police my body.

Rapidly, I internalized the tenets of wellness culture, expunging from my diet anything that could possibly blemish my health. Desperate to avoid food I deemed dirty, I falsely told friends, doctors, and teachers that I was sensitive to gluten and dairy. I further banished bananas and mangoes for being “too sugary,” tomatoes and eggplants for being “too inflammatory,” and chickpeas for “impeding nutrient absorption.”

No food was immune to my castigation as I pored over wellness articles and platforms, unearthing purported drawback after purported drawback.

I concurrently embraced the notion that “sitting is the new smoking;” in fact, my sheer terror about being sedentary likely outshadowed my foreboding about eating “unclean.” I thereby meticulously choreographed my days; I ate standing up, I fidgeted in class, I walked in circles around the house. Sitting one extra minute or taking one fewer step than planned inevitably catapulted me into panicked tears.

Thoughts of food, movement, and body soon annexed all my mental real estate, and I grew deeply socially withdrawn. I frequently questioned whether I could endure another day living this way. Halfway through eighth grade, I dropped out to become homeschooled, stunning the kids I had grown up with. The irony of it all did not escape me—I was in the worst physical and mental state of my life because I had so fanatically pursued superlative health.

By the time I dined at Lucky Lee’s in 2019, my physician had judged me to be fully recovered. Yet the very fact that I was seeking a “health-ified” alternative to the cultural food of my childhood was a testament to my fragmented rehabilitation. Sure, I had regained the weight I lost, but I had done little to dismantle my fallacious notions regarding wellness. I was still eschewing real crackers in favor of “clean” almond and cassava flour proxies; I simply ate more of the “clean” surrogates to ensure I could gain weight while adhering to unmalleable food and exercise dictates. This was an indisputable case of orthorexia, masquerading as a seductive, socially laudable feat of “discipline” and “health-consciousness”.

Given the high socio-political and cultural premium we place on “health,” the burgeoning of orthorexia is unfortunately not a surprise. While we may denounce overt calorie counting and dieting under the guise of “body positivity,” we now incessantly preach “healthy” living.

Wellness is rendered a veritable aesthetic—a token of social capital—and we are obliged to “perform” health to be good citizens worthy of basic belonging.

Implicit in the equation of well-being with personal character (and the eulogization of diet and exercise as golden tickets to wellness) is the fallacy that health falls entirely under personal control. When it comes to health, we promulgate a narrative of rugged individualism, localizing the onus of responsibility. For instance, we may attribute poor health outcomes to negligence or insufficient impulse control while ascribing favorable outcomes to meritorious self-restraint and virtue. Rarely, however, do we consider how intersecting systems of white supremacy, anti-fatness, homophobia, transphobia, ableism, etc. impair individual and population well-being.

In order to truly recover from my eating disorder, I’ve thus found it necessary to interrogate my deep-seated convictions about health through a critical, justice-oriented lens. Reflecting on my experiences at Lucky Lee’s and the prevalent deprecation of BIPOC cuisine, I’ve specifically reckoned with the weaponization of food as a tool of colonialism.

A bit of historical context: in the 15th century, European colonizers contended they were dying in the “New World” due to a dearth of healthful European foods (bread, olives, meat, wine, etc.). Deeming the bodies of indigenous folks fundamentally corrupt, they maintained that consuming indigenous foods would corrode their European essence, barbarizing them and polluting them with sin. The moralized dichotomy between “good, proper” (e.g, European) foods and “inferior, wrong” (e.g., indigenous) foods—the pernicious nutritional dogma of “you are what you eat”—hence emerged.

Reading about the obsession with “ensuring settlers’ access to the elements of a proper European diet” was staggering, for it so strikingly mirrored my own disordered thinking.

Just as colonists acutely feared indigenization through the consumption of “impure”, non-European foods, I feared bodily adulteration by some indestructible foreign substance every time I consumed the “unclean” foods of my culture.

I felt corrupted, indeed dirty, whenever I ate “unhealthily” and was thus driven to eradicate all possible sources of impurity, to “cleanse” myself of imagined pollutants through strict dietary measures and rigorous workouts.

By considering how white supremacy and colonialism shaped my struggles with an eating disorder (and given the many privileges I harbor as a thin, cis, able-bodied young woman financially supported by my family), I’ve been able to find genuine HEALing, and I’ve grown into a passionate body liberation and health justice activist. I run the Instagram platform @alexfoodfreedom; I work to champion more equitable public health legislation as a policy advocate with Harvard STRIPED; and, of course, I’ve had the honor of joining the amazing Project HEAL family as our blog manager.

Here’s to breaking down barriers to life-saving, identify-affirming care; dismantling hierarchies of bodies; and reenvisioning an ethos of collective wellness—because all bodies are good bodies; we’re better together; and recovery truly renews life with joy, connection, and meaning.

Alexandra Xu (she/her) is a high school senior in New Jersey. After struggling with and recovering from orthorexia, she knows the importance of ensuring equitable access to culturally competent, trauma-informed eating disorder care. In addition to serving as Project HEAL’s Blog Manager, she runs the Instagram platform @alexfoodfreedom, where she writes and instigates discussions on eating disorders, body liberation, health, and social justice. She also works with Harvard STRIPED to spearhead more equitable youth mental health legislation in NJ. Her writing has been featured in Wear Your Voice magazine and honored with a National Gold Medal in the Scholastic Art & Writing Awards. In her free time, Alexandra loves playing piano and soccer, singing, listening to music, and spending time in nature.